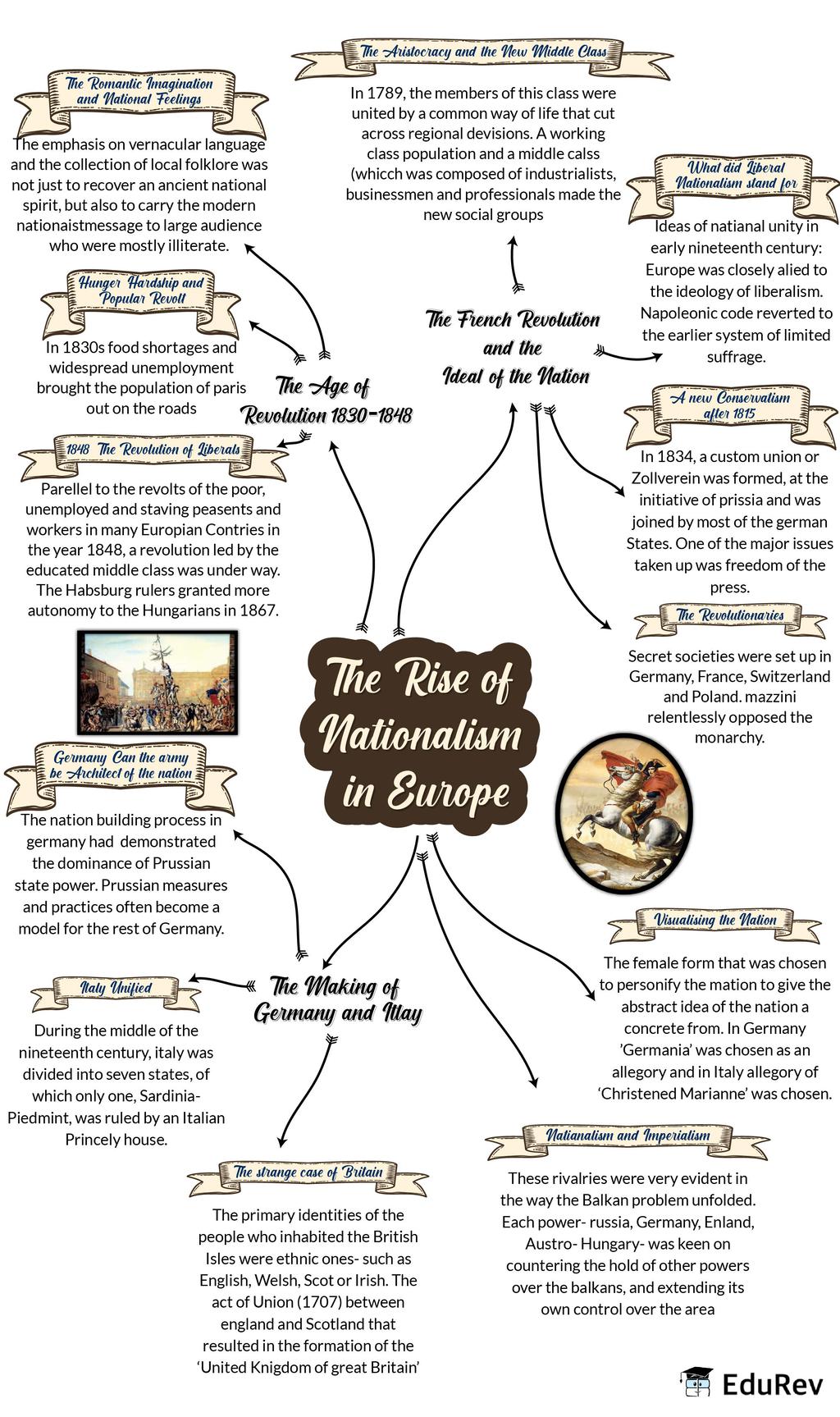

- During the nineteenth century, nationalism emerged as a force that brought about sweeping changes in the political and mental world of Europe. The end result of these changes was the emergence of the nation-state in place of the multi-national dynastic empires of Europe.

- The concept and practices of a modern state, in which a centralized power exercised sovereign control over a clearly defined territory, had been developing over a long period of time in Europe.

- But a nation-state was one in which the majority of its citizens, and not only its rulers, came to develop a sense of common identity and shared history or descent.

- This commonness did not exist from time immemorial; it was forged through struggles, through the actions of leaders and the common people.

Some Important Terms

Absolutist – Literally, a government or system of rule that has no restraints on the power exercised. In history, the term refers to a form of monarchical government that was centralized, militarized, and repressive

Utopian – A vision of a society that is so ideal that it is unlikely to actually exist

Plebiscite – A direct vote by which all the people of a region are asked to accept or reject a proposal

- The first clear expression of nationalism came with the French Revolution in 1789. France was a full-fledged territorial state in 1789 under the rule of an absolute monarch.

- French Revolution gave way to the political and constitutional changes that led to the transfer of sovereignty from the monarchy to a body of French citizens.

- The revolution proclaimed that it was the people who would henceforth constitute the nation and shape its destiny.

- The French revolutionaries introduced various measures and practices that could create a sense of collective identity amongst the French people.

- The ideas of la Patrie (the fatherland) and le citoyen (the citizen) emphasized the notion of a united community enjoying equal rights under a constitution.

➢ Some changes that occurred

- A new French flag, the tricolour, was chosen to replace the former royal standard.

- The Estates-General was elected by the body of active citizens and renamed the National Assembly.

- New hymns were composed, oaths taken and martyrs commemorated, all in the name of the nation.

- A centralized administrative system was put in place and it formulated uniform laws for all citizens within its territory.

- Internal customs duties and dues were abolished and a uniform system of weights and measures was adopted.

- Regional dialects were discouraged and French, as it was spoken and written in Paris, became the common language of the nation.

➢ Impact on other European nations

- When the news of the events in France reached the different cities of Europe, students and other members of the educated middle classes began setting up Jacobin clubs.

- Their activities and campaigns prepared the way for the French armies which moved into Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, and much of Italy in the 1790s.

- In 1797, Napoleon invaded Italy, and Napoleonic wars began.

- A wide territory came under Napoleon’s control and introduced many of the reforms that he had already introduced in France.

- Although Napoleon had destroyed democracy in France, in the administrative field he had incorporated revolutionary principles in order to make the whole system more rational and efficient.

- The Civil Code of 1804 – usually known as the Napoleonic Code – removed all privileges based on birth, established equality before the law, and secured the right to property. This code was extended to regions under French control.

- In the Dutch Republic, in Switzerland, in Italy, and in Germany, Napoleon simplified administrative divisions, abolished the feudal system, and freed peasants from serfdom and manorial dues.

- In the towns, guild restrictions were removed

- Transport and communication systems were improved. Peasants, artisans, workers, and new businessmen enjoyed new-found freedom.

- Businessmen and small-scale producers of goods, in particular, began to realize that uniform laws, standardized weights, and measures, and a common national currency would facilitate the movement and exchange of goods and capital from one region to another.

- In many places such as Holland and Switzerland, as well as in certain cities like Brussels, Mainz, Milan, and Warsaw, The initial enthusiasm soon turned to hostility, as it became clear that the new administrative arrangements did not go hand in hand with political freedom. Increased taxation, censorship, forced conscription into the French armies required to conquer the rest of Europe, all seemed to outweigh the advantages of the administrative changes.

- During the mid-eighteenth century, there were no ‘nation-states’ in Europe as we see today.

- Germany, Italy, and Switzerland were divided into kingdoms, duchies, and cantons whose rulers had their autonomous territories.

- Eastern and Central Europe were under autocratic monarchies within where diverse people lived who did not see themselves as sharing a collective identity or a common culture. They even spoke different languages and belonged to different ethnic groups.

- For example, the Habsburg Empire that ruled over Austria-Hungary has included the Alpine regions – the Tyrol, Austria, and the Sudetenland – as well as Bohemia, where the aristocracy was predominantly German-speaking.

- In Hungary, half of the population spoke Magyar while the other half spoke a variety of dialects.

- The differences did not easily promote a sense of political unity.

➢ The Aristocracy and The New Middle Class

- Landed aristocracy was the social and politically dominant class on the continent. It was a numerically small group.

- Aristocrats: had a common way of life that cut across regional divisions, owned estates in the countryside and also town-houses, spoke French for purposes of diplomacy and in high society. Their families were often connected by ties of marriage.

- Peasantry formed the bulk of the population. To the west, the bulk of the land was farmed by tenants and small owners, while in Eastern and Central Europe the pattern of landholding was characterized by vast estates that were cultivated by serfs.

- In Western and parts of Central Europe due to the growth of industrial production and trade towns and commercial classes emerged, · Industrialization began in England in the second half of the eighteenth century, but in France and parts of the German states, it occurred only during the nineteenth century.

- New social groups emerged: a working-class population and middle classes made up of industrialists, businessmen, professionals.

- In Central and Eastern Europe, these groups were smaller in number till the late nineteenth century.

- It was among the educated, liberal middle classes that ideas of national unity following the abolition of aristocratic privileges gained popularity.

➢ What did Liberal Nationalism Stand for?

- The term ‘liberalism’ derives from the Latin root liber, meaning free.

- For the new middle classes, liberalism stood for freedom for the individual and equality of all before the law.

- Politically, it emphasized the concept of government by consent.

- Since the French Revolution, liberalism had stood for the end of autocracy and clerical privileges, a constitution, and representative government through parliament. Nineteenth-century liberals also stressed the inviolability of private property.

- Yet, equality before the law did not necessarily stand for universal suffrage. In revolutionary France, the right to vote and to get elected was granted exclusively to property-owning men.

- Men without property and all women were excluded from political rights.

- Napoleonic Code went back to limited suffrage and reduced women to the status of a minor, subject to the authority of fathers and husbands.

- In the economic sphere, liberalism stood for the freedom of markets and the abolition of state-imposed restrictions on the movement of goods and capital.

- Conditions like customs barriers and customs duty and different systems of weights and measurements in different regions were viewed as obstacles to economic exchange and growth by the new commercial classes, who argued for the creation of a unified economic territory allowing the unhindered movement of goods, people and capital.

- In 1834, a customs union or Zollverein was formed at the initiative of Prussia and joined by most of the German states.

- The union abolished tariff barriers and reduced the number of currencies from over thirty to two. Mobility was enhanced by a network of railways.

➢ A New Conservatism after 1815

Conservatism – A political philosophy that stressed the importance of tradition, established institutions, and customs and preferred gradual development to quick change.

- Following the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, European governments were driven by a spirit of conservatism.

- Conservatives believed that established, traditional institutions of state and society – like the monarchy, the Church, social hierarchies, property, and the family – should be preserved.

- Most conservatives, however, did not propose a return to the society of pre-revolutionary days.

- Rather, they realized, from the changes initiated by Napoleon, that modernization could in fact strengthen traditional institutions like the monarchy. It could make state power more effective and strong.

- A modern army, an efficient bureaucracy, a dynamic economy, the abolition of feudalism and serfdom could strengthen the autocratic monarchies of Europe.

➢ The Congress of Vienna, 1815

- In 1815, representatives of the European powers – Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria – who had collectively defeated Napoleon, met at Vienna to draw up a settlement for Europe.

- The Congress was hosted by the Austrian Chancellor Duke Metternich.

- The delegates drew up the Treaty of Vienna of 1815 with the object of undoing most of the changes that had come about in Europe during the Napoleonic wars.

- The Bourbon dynasty, which had been deposed during the French Revolution, was restored to power, and France lost the territories it had annexed under Napoleon.

- A series of states were set up on the boundaries of France to prevent French expansion in the future.

(i) Kingdom of the Netherlands, which included Belgium, was set up in the north.

(ii) Genoa was added to Piedmont in the south.

(iii) Prussia was given important new territories on its western frontiers.

(iv) Austria was given control of northern Italy. - The German confederation of 39 states that had been set up by Napoleon was left untouched.

- In the east, Russia was given part of Poland while Prussia was given a portion of Saxony.

➢ Main Intention of The Congress

- The main intention was to restore the monarchies that had been overthrown by Napoleon and create a new conservative order in Europe.

- Conservative regimes set up in 1815 were autocratic.

- They did not tolerate criticism and dissent and sought to curb activities that questioned the legitimacy of autocratic governments.

- Most of them imposed censorship laws to control what was said in newspapers, books, plays, and songs and reflected the ideas of liberty and freedom.

➢ The Revolutionaries

- During the years following 1815, the fear of repression drove many liberal-nationalists

- underground.

- Secret societies sprang up in many European states to train revolutionaries and spread their ideas.

- Most of these revolutionaries also saw the creation of nation-states as a necessary part of this struggle for freedom.

- One such individual was the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini. He founded two underground societies, first, Young Italy in Marseilles, and then, Young Europe in Berne, whose members were like-minded young men from Poland, France, Italy, and the German states.

- Mazzini believed that God had intended nations to be the natural units of mankind. So Italy could not continue to be a patchwork of small states and kingdoms.

- Following his model, secret societies were set up in Germany, France, Switzerland, and Poland.

- Liberalism and nationalism came to be increasingly associated with the revolution in many regions of Europe such as the Italian and German states, the provinces of the Ottoman Empire, Ireland, and Poland.

- These revolutions were led by the liberal-nationalists belonging to the educated middle-class elite, among whom were professors, schoolteachers, clerks, and members of the commercial middle classes.

- The first upheaval took place in France in July 1830. The Bourbon kings who had been restored to power during the conservative reaction after 1815, were now overthrown by liberal revolutionaries who installed a constitutional monarchy with Louis Philippe at its head.

- The July Revolution sparked an uprising in Brussels which led to Belgium breaking away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

➢ Greek War of Independence

- Greece had been part of the Ottoman Empire since the fifteenth century. The growth of revolutionary nationalism in Europe triggered a struggle for independence amongst the Greeks which began in 1821.

- Nationalists in Greece got support from other Greeks living in exile and also from many West Europeans who had sympathies for ancient Greek culture. · The Treaty of Constantinople of 1832 recognized Greece as an independent nation.

➢ The Romantic Imagination and National Feeling

- Culture played an important role in creating the idea of the nation: art and poetry, stories and music helped express and shape nationalist feelings.

- Romanticism: a cultural movement that sought to develop a particular form of nationalist sentiment.

- Romantic artists and poets generally criticized the glorification of reason and science and focused instead on emotions, intuition, and mystical feelings. Their effort was to create a sense of a shared collective heritage, a common cultural past, as the basis of a nation.

- Romantics such as the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) claimed that true German culture was to be discovered among the common people – das volk and through folk songs, folk poetry, and folk dances that the true spirit of the nation (volksgeist) was popularized.

- The emphasis on vernacular language and the collection of local folklore was not just to recover an ancient national spirit, but also to carry the modern nationalist message to large audiences who were mostly illiterate.

- Poland no longer existed as an independent territory and had been partitioned at the end of the eighteenth century by the Great Powers – Russia, Prussia, and Austria but the national feelings were kept alive through music and language. Karol Kurpinski, for example, celebrated the national struggle through his operas and music, turning folk dances like the polonaise and mazurka into nationalist symbols.

- Language too played an important role in developing nationalist sentiments.

- The use of Polish came to be seen as a symbol of the struggle against Russian dominance.

➢ Hunger, Hardship, and Popular Revolt

- The 1830s were years of great economic hardship in Europe. The first half of the nineteenth century saw an enormous increase in population all over Europe.

- In most countries, there were more seekers of jobs than employment. Population from rural areas migrated to the cities to live in overcrowded slums. Small producers in towns were often faced with stiff competition from imports of cheap machine-made goods from England, where industrialization was more advanced than on the continent.

- In those regions of Europe where the aristocracy still enjoyed power, peasants struggled under the burden of feudal dues and obligations. In 1848, food shortages and widespread unemployment brought the population of Paris out on the roads.

- Barricades were erected and Louis Philippe was forced to flee.

- A National Assembly proclaimed a Republic, granted suffrage to all adult males above 21 and guaranteed the right to work.

- National workshops to provide employment were set up.

- Earlier, in 1845, weavers in Silesia had led a revolt against contractors who supplied the raw material and gave them orders for finished textiles but drastically reduced their payments.

➢ 1848: The Revolution of The Liberals

- Events of February 1848 in France had brought about the abdication of the monarch and a republic based on universal male suffrage had been proclaimed.

- In other parts of Europe where independent nation-states did not yet exist – such as Germany, Italy, Poland, the Austro-Hungarian Empire – men and women of the liberal middle classes combined their demands for constitutionalism with national unification.

- They took advantage of the growing popular unrest to push their demands for the creation of a nation-state on parliamentary principles – a constitution, freedom of the press, and freedom of association.

- In the German regions, a large number of political associations came together in the city of Frankfurt and decided to vote for an all-German National Assembly.

- On 18 May 1848, 831 elected representatives marched in a festive procession to take their places in the Frankfurt parliament convened in the Church of St Paul. They drafted a constitution for the German nation to be headed by a monarchy subject to a parliament.

- While the opposition of the aristocracy and military became stronger, the social basis of parliament eroded.

- The parliament was dominated by the middle classes who resisted the demands of workers and artisans and consequently lost their support.

- In the end, troops were called in and the assembly was forced to disband.

- The issue of extending political rights to women was a controversial one within the liberal movement, in which large numbers of women had participated actively over the years. Women had formed their own political associations, founded newspapers, and taken part in political meetings and demonstrations.

- Despite this, they were denied suffrage rights during the election of the Assembly. When the Frankfurt parliament convened in the Church of St Paul, women were admitted only as observers to stand in the visitors’ gallery.

- Though conservative forces were able to suppress liberal movements in 1848, they could not restore the old order.

- Monarchs were beginning to realize that the cycles of revolution and repression could only be ended by granting concessions to the liberal-nationalist revolutionaries.

- Serfdom and bonded labour were abolished both in the Habsburg dominions and in Russia. The Habsburg rulers granted more autonomy to the Hungarians in 1867.

Feminist – Awareness of women’s rights and interests based on the belief of the social, economic, and political equality of the genders.

Ideology – System of ideas reflecting a particular social and political vision

➢ Germany – Can the Army Be the Architect of a Nation?

- After 1848, nationalism in Europe moved away from its association with democracy and revolution.

- Nationalist sentiments were often mobilized by conservatives for promoting state power and achieving political domination over Europe.

- Nationalist feelings were widespread among middle-class Germans, who in 1848 tried to unite the different regions of the German confederation into a nation-state governed by an elected parliament.

- This liberal initiative to nation-building was, however, repressed by the combined forces of the monarchy and the military, supported by the large landowners (called Junkers) of Prussia.

- From then on, Prussia took on the leadership of the movement for national unification.

- Otto von Bismarck was the architect of the unification process carried out with the help of the Prussian army and bureaucracy.

- Three wars over seven years – with Austria, Denmark, and France – ended in Prussian victory and completed the process of unification.

- In January 1871, the Prussian king, William I, was proclaimed German Emperor in a ceremony held at Versailles. Otto von Bismarck gathered in the unheated Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles to proclaim the new German Empire headed by Kaiser William I of Prussia.

- The nation-building process in Germany had demonstrated the dominance of Prussian state power where the strong emphasis was placed on modernizing the currency, banking, legal and judicial systems in Germany. Prussian measures and practices often became a model for the rest of Germany.

➢ Italy Unified

- Italians were scattered over several dynastic states as well as the multi-national Habsburg Empire.

- During the middle of the nineteenth century, Italy was divided into seven states, of which only one, Sardinia-Piedmont, was ruled by an Italian princely house. The north was under Austrian Habsburgs, the center was ruled by the Pope and the southern regions were under the domination of the Bourbon kings of Spain.

- The Italian language had not acquired one common form and still had many regional and local variations.

- During the 1830s, Giuseppe Mazzini had sought to put together a coherent program for the unitary Italian Republic.

- The failure of revolutionary uprisings both in 1831 and 1848 prompted Sardinia-Piedmont under its ruler King Victor Emmanuel II to unify the Italian states through the war as it could bring about economic development and political dominance.

- Chief Minister Cavour who led the movement to unify the regions of Italy was a wealthy and educated member of the Italian elite and spoke French much better than he did Italian.

- Through a tactful diplomatic alliance with France engineered by Cavour, Sardinia-Piedmont succeeded in defeating the Austrian forces in 1859.

- Apart from regular troops, a large number of armed volunteers under the leadership of Giuseppe Garibaldi joined the fray. In 1860, they marched into South Italy and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and succeeded in winning the support of the local peasants in order to drive out the Spanish rulers.

- In 1861 Victor Emmanuel II was proclaimed king of united Italy. Much of the Italian population, among whom rates of illiteracy were very high, remained blissfully unaware of liberal nationalist

ideology.

➢ The Strange Case of Britain

- In Britain, the formation of the nation-state was not the result of a sudden upheaval or revolution.

- There was no British nation prior to the eighteenth century.

- The primary identities of the people who inhabited the British Isles were ethnic ones – such as English, Welsh, Scot, or Irish. All of these ethnic groups had their own cultural and political traditions.

- The English parliament, which had seized power from the monarchy in 1688 at the end of a protracted conflict, was the instrument through which a nation-state, with England at its center, came to be forged.

- The Act of Union (1707) between England and Scotland resulted in the formation of the ‘United Kingdom of Great Britain’.

- England was able to impose its influence on Scotland. The British parliament was dominated by its English members.

- Scotland’s distinctive culture and political institutions were systematically suppressed. The Catholic clans that inhabited the Scottish Highlands suffered terrible repression whenever they attempted to assert their independence. The Scottish Highlanders were forbidden to speak their Gaelic language or wear their national dress, and large numbers were forcibly driven out of their homeland.

- In Ireland, a deep divide existed between Catholics and Protestants. The English helped the Protestants of Ireland to establish their dominance over a largely Catholic country. Catholic revolts against British dominance were suppressed.

- After a failed revolt led by Wolfe Tone and his United Irishmen (1798), Ireland was forcibly incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1801.

- A new ‘British nation’ was forged through the propagation of a dominant English culture. The symbols of the new Britain – the British flag (Union Jack), the national anthem (God Save Our Noble King), the English language – were actively promoted.

Ethnic – Relates to a common racial, tribal, or cultural origin or background that a community identifies with or claims

- Artists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries found a way out by personifying a nation. In other words, they represented a country as if it were a person.

- Nations were then portrayed as female figures.

- The female form that was chosen to personify the nation did not stand for any particular woman in real life; rather it sought to give the abstract idea of the nation a concrete form. That is, the female figure became an allegory of the nation.

- During the French Revolution artists used the female allegory to portray ideas such as Liberty, Justice, and the Republic.

- Germania became the allegory of the German nation. In visual representations, Germania wears a crown of oak leaves, as the German oak stands for heroism.

No comments:

Post a Comment